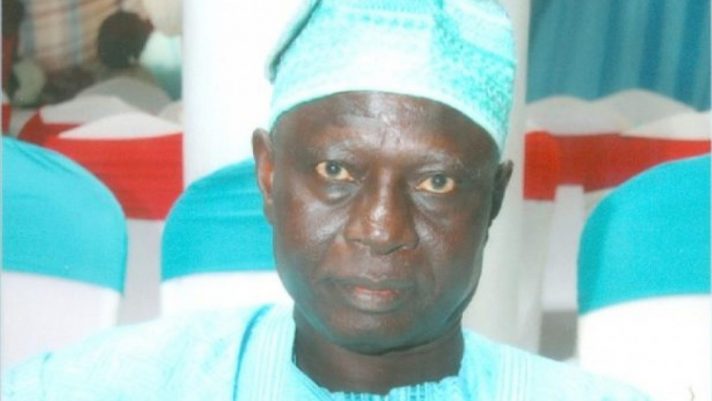

The death of Professor Alex Gboyega, a retired professor of political science at the University of Ibadan is the latest in the series of deaths of prominent Nigerians that have overshadowed the month of January 2022.

In our relational and crisscrossing networks of significance, the shocking news of deaths hits us at different levels the same way we relate at different levels with those around us.

I am connected with the late Prof. Gboyega at many levels, personal and intellectual. Prior to hearing about his shocking death, I had been involved in the National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPSS)’s move to invite him as a guest speaker at the Senior Executive Course (SEC) 44 in view of its 2022 theme of local governance, Prof. Gboyega’s forte. He apologized that he would not be able to attend given that he had just undergone surgery and needed to convalesce. We later saw few hours after that engagement the news on social media that he had passed on.

Alex Gboyega, alongside Ladipo Adamolekun, emerged from the former University of Ife scholar-practitioner framework of engagement, which was the basis of the praxis created for the Chief Simeon Adebo-led western region civil service. And this model of engagement demanded that there must be serious attention given to recruitment in a way that adds to the functionality of the institute of administration as a complement of the practice of public administration in the public service. Thus, to concretize the model, Prof. Gboyega enlisted my late uncle, Chief Alfred Olaopa, and Chief Augustus Adebayo, to teach courses in local government. Chief Augustus would later teach me public administration at the University of Ibadan. So, in a fundamental way, my fascination with the scholar-practitioner model of engagement commenced right from my critical observation of dynamics of which Prof. Alex Gboyega was a significant part. Much more fundamental to Prof. Gboyega’s legacy is the idea of local government and governance that he started running with right from the commencement of his scholarship.

His specialization straddled local governance, public administration and indigenous political institutions. These thematic concerns tell a coherent and significant story about Prof. Gboyega’s research portfolio that speaks to the core of Nigeria’s postcolonial and democratic malaise. Right from her independence, Nigeria has been faced with the challenge of governing a state made up of plural constituents. Or, to rephrase, the challenge is that of deploying the federal framework as the most formidable structure within which Nigeria could achieve national integration and development. As early as 1981, Alex Gboyega, in “Intergovernmental relations in Nigeria: Local government and the 1979 Nigerian Constitution,” was already fascinated with the elevated positioning of the local government which the 1979 Constitution took from the 1976 Dasuki local government reform.

In a 1991 essay, “Protecting local governments from arbitrary state and federal interference: What prospects for the 1990s?” Gboyega already started entertaining doubts about the possibility of limiting state and federal undermining of the autonomy of the local governments the number of which was fixed at 453 by the 1989 Constitution. And in his 2003 inaugural lecture, Prof. Gboyega located the conceptual possibilities of democracy and development in the handling of local governance. Contrary to the 1976 local government reform enshrined in the 1979 Constitution, the present state of the local governments and local governance has become dismal. And this is all the more so because Nigeria’s democratic experimentation commenced in 1999 without the complement of local governance and its distinctive elements, from subsidiarity to social capital.

Apart from the delineation of duties into the executive, concurrent and residual, which leaves the local government bereft of functional responsibilities, the states in Nigeria cast their shadows on their respective local government. For instance, despite the number of constitutionally assigned sources of revenue generation and collection, local governments’ fiscal bases are regularly eroded by the encroachment of the states. Thus, the erosion of local government autonomy has become fundamental to the question of federalism and the survival of Nigeria’s democratic governance. It has become axiomatic that local governance is fundamental to the consolidation and sustenance of democracy everywhere. Local governance facilitates the grassroots participation of the people who are the most fundamental factor in governance.

Indeed, the local governments constitute the framework for testing the transparency and responsiveness of government institutions. This is where the concepts of subsidiarity and social capital become fundamental in understanding local governance. The subsidiarity principle is targeted at undermining the centralization dynamics that are at work in the lopsidedness of the Nigerian federal constitution. Subsidiarity insists that whatever issues can be handled at the local and grassroots level must not, as a matter of fact, be centralized out of such contexts. As a democratic principle, subsidiarity becomes imperative for local participation in governance matters. As a development initiative, it resolves three basic governance problems: (i) it facilitates the ownership of development insights and paradigms; (ii) it facilitates the instigation of self-reliance through the deployment of local ideas and innovation; and (iii) it enables a bottom-up governance approach which in the long run helps the government itself strengthens its legitimacy quotient in the eye of the people.

Within the context of local governance, the idea of subsidiarity coherently attaches to that of social capital as a framework for making local governance and grassroots indigenous institutions work for the well-being of the people.

Social capital is founded on the significance and roles of networks, communities, collaborations, connectives, and the reciprocal values that are derivable from their interconnectedness and their function. Social capital is the values and benefits generated by the cooperative endeavors of people within any institutional contexts. Thus, once subsidiarity is taken for granted as a constitutional principle, the social capital dynamic springs to action in facilitating the many networks, communities and collaborations for an active communal mobilization for development. Unfortunately, the functionality of the local institutions and the various networks have been smothered by the asphyxiation of the local governments by a constitution that disdains decentralization as a development dynamic.

The political oversight of the local government by the states, especially, is starving local governance of its many potentialities even as the citizens’ expectations of local governments and democratic governance are growing. If democracy needs the grassroots to survive, then there is a compelling need to link Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) to the viability of local government for that tier of government to be truly developmental. Indeed, CBOs have served as the basis for vibrant self-help, service provision and as a coping mechanism to cater to people’s expectations far above the capacities and capabilities of the state system. People are now used to ground their security networks in the form of vigilante and neighbourhoods watch groups; maintain their roads; and initiate economic empowerment. Historically, for example, the Esusu microfinance scheme has become a veritable feature of modern financial assistance. The danger is that usually, especially within the context of the Nigerian state, people’s search for developmental meaning in the grassroots is carried out outside of the reach of the state; as a concrete performance of the people’s collective rejection of the state.

The demise of Prof. Alex Gboyega, as well as the significance of his scholarship on local government, poignantly underscores, more than ever before, the urgent need for a paradigm shift in a grassroots-propelled and constitutionally-sanctioned governance initiative that has the capacity to transform the enormous wealth and networks of the rural areas and local communities into development points. This is where the optimum communities (OPTICOM) project of Professors Ojetunji Aboyade and Akin Mabogunje at Aawe in Afijio LGA of Oyo State resurfaces again as a reprofiling strategy that builds rural infrastructures as developmental models of local governance. As Prof. Gboyega adequately and stridently canvassed, bringing the local government back into the democratic governance framework is a constitutional matter. Indeed, it forms a fundamental dimension of what restructuring stands for.

Rethinking the place of the local governments in the constitutional provision for intergovernmental relations translate into the willingness to place the people at the centre of democratic development in Nigeria. It is as simple as that. It is an admission that Nigeria’s fixation with the top-down and centralized development strategy has failed. And that local governance and the empowerment of indigenous institutions and grassroots networks and collaborations stand at the heart of national development. National development has failed consistently because development strategies of various hues have been forced down the throats of local communities who have no reason whatsoever to own them or do something meaningful with them to enhance their well-being.https://38bbe0419f4bbeebf1a52640664b7238.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

Flowing from global ideological offerings, Nigeria has become a captive of say, the Washington Consensus that insists that development must be imposed on hapless citizens who have no say in the matter of their own betterment. Thus, while the local governments are constitutionally emasculated within, local governance is ideologically strangulated from without. No wonder, since independence, Nigeria has been searching not only for a development plan but also for an institutional reform framework by which to achieve national integration. Activating the local government is equally a policy reform initiative. The constitutional issue about the local government would be firmed up by stringent attention to the policy incorporated into the Local Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (LEEDS). This policy opens up the local communities for socioeconomic growth through the participation of government, nongovernmental agencies and civil society.

In strengthening the institutional framework for making local governance functioning as a democratic imperative, democracy itself becomes the foremost beneficiary since it makes possible not only the emergence of higher quality of candidates to local offices but also the active participation of citizens in electoral matters that would then have become a significant complement to development issues for them.

On the one hand, local governments can be incentivized by grants allocations through the periodic ranking of LGAs based on stakeholders-validated service standards that are published and celebrated. And on the other hand, and as a correlate, this generates the basis for calibrating frameworks for aligning such self-help schemes as neighbourhood watch, waste collection, water supply, sanitation, etc. service provisions system with government arrangements under a public-public partnership (PPP). Eventually, it is through local governance and its many potentials that we actually begin to see democratic governance unfold. That is the essence of the scholarship of Professor Alex Gboyega.

Olaopa is a retired Federal Permanent Secretary and professor of public administration, National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPSS), Kuru, Jos. tolaopa2003@gmail.com